Hemochromatosis, Iron Overload, Hemopause, and CelticCurse dot org: an update for 2024

The Work Begins Here: Teaching the world about the Celtic Curse.

I began that first article with this statement: "The more people know about hemochromatosis, a genetic condition often referred to as Celtic Curse, the fewer will suffer needlessly and die tragically."That statement remains true today, more than 14 years after I wrote it. The effort to fight hereditary hemochromatosis by informing people about this surprising common genetic mutation—and the potentially fatal condition of iron overload that it can create—needs to continue in 2024.

Thankfully, over the last decade a growing number organizations and online efforts have appeared and expanded to reach more and more people. Here are just a few of them, from around the world:

- Hemochromatosis.org

- Iron Disorders Institute

- Haemochromatosis UK

- The Irish Haemochromatosis Association

- American Hemochromatosis Society

- Canadian Hemochromatosis Society

(provides international a list of support organizations)

Over the last 14 years I managed to publish about 50 articles here on this site, covering the symptoms, treatment, and implications of hereditary hemochromatosis, in general and for some specific demographics. That was fewer articles than I had originally hoped to write, but life—including some of the effects of my partner's iron overload—got in the way.

Fortunately, I was able to supplement my awareness-raising efforts on this website with a Facebook page. That page has achieved nearly 10,000 "likes" so far. Information posted there reaches hundreds of people every month, sometimes thousands. Hopefully, these combined effort have led to more people getting diagnosed earlier and treated better.

There's so much more to be done

Sadly, one statement that I made in that first article, back in 2010, has not proven entirely correct. At that point in time I had been researching hemochromatosis for about a year and a half, reading books and journal articles, attending several conferences, and talking to lots of people. Based on that, it seemed reasonable to say:

"The only real obstacle to universal detection, treatment, and elimination of this potentially deadly condition is a lack of information among doctors and the general population."

But since then I have learned that there are other serious obstacles to reducing the tragic impact of hemochromatosis; most notable are these two:

- the patriarchal arrogance of some (too many) doctors

- the negative impact of pharmaceutical companies

Unfortunately, these two factors often interact. For example, patriarchal doctors tend to under-diagnose hemochromatosis in women. This tends to diminish the impact of the condition, making it less visible to researchers and the people who fund them.

Over the years I have tried to address this particular problem, notably by raising awareness of what I call hemopause, a syndrome that I first identified back in 2012; it afflicts women entering menopause with undiagnosed hereditary hemochromatosis. Some years ago I made a website to address hemopause specifically.

The negative impact of pharmaceutical companies is their tendency to draw funding away for research into, and diagnosis of, hemochromatosis. Drug companies make most of their money by selling products that treat symptoms or their causes; that's what drives and directs their spending on medical research. The cause of hemochromatosis symptoms is iron overload, for which a cheap and effective treatment already exists: drawing blood. In other words, many other illnesses offer more fertile ground for research into readily monetizable treatments than does hemochromatosis.

Removing blood—phlebotomy or venesection—is one of the least expensive and most widely available medical procedures in the world. We often call the process giving blood, because blood is valuable. Blood from hemochromatosis patients can be used like any other blood, and in fact may be even more valuable than regular blood.

All of this is bad good news for drug companies that are only interested in funding research into conditions for which a revenue-generating treatment can be developed and sold to people suffering from those conditions.

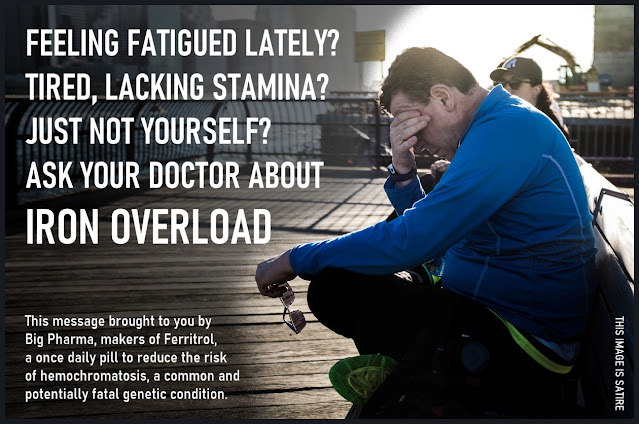

I apologize if this sounds cynical, but my goal is to be realistic. For example, here is a realistic scenario: a drug company develops a pill to treat the iron overload caused by hemochromatosis. Studies shows it to be more effective than phlebotomy. FDA approval is granted for use in the USA. There are potentially millions of customers in America—people suffering from iron overload—but many of them don't know they need this pill. What does the drug company do?

If you've spent time in America in the last few decades, you already know the answer: massive ad campaigns that use the tried and tested strategy of "ask your doctor about X." Nobody would be surprised to see an outbreak of ads like this one I made for Ferritrol, a fictitious, pill-based pharmaceutical treatment for people with hemochromatosis.

In other words, if there were pills you could sell to treat hemochromatosis, the makers of those pills would raise hemochromatosis awareness faster and higher than volunteers and non-profit organizations ever will. That would probably result in more widespread genetic testing for the HFE mutation that signals susceptibility to iron overload, which is something that the fight against hemochromatosis desperately needs.

The good news in 2024 is that iron overload can still be safely and effectively treated by drawing blood, which is a free service in many countries. The problem is that too many people with the genetic disposition to accumulate iron are unaware they have it, and not enough is being done to identify those people.

What can we do?

We can reduce suffering and save lives by continuing to spread awareness of hemochromatosis. This is still a very viable strategy, and you can do a lot of awareness raising for very little cost. Here are 10 things you might want to try:- Learn about hemochromatosis

- Tell people about hemochromatosis

- Ask your doctor about hemochromatosis (particularly if you have Irish or Celtiuc ancestry)

- Share this page and the list of support organizations above

- Download information sheets and posters from the Iron Disorders Institute

- Distribute this information wherever you can

- Like the Hemochromatosis page on Facebook

- Visit the hemopause website

- Donate to a hemochromatosis support group

- Consider getting a genetic test for hemochromatosis.

Comments

Post a Comment